02.06.18

As a cellist myself, I can't really pretend to be impartial when I say that this is by far and away my favourite instrument to record. What other instrument represents the human voice and soul so perfectly?

Over the years I have collaborated with many well-established masters of the instrument: Paul Watkins, Albert Gerhardt, Tim Hughes, Leonid Gorokhov and Alexander Ivashkin, to name a few. In June, however, I was asked to produce a recording with a cellist whose career is only just beginning. Constantin Macherel, a former student of Raphael Wallfisch, was making his very first orchestral recording.

This quiet young man played virtuosic works by Servais, Franchomme, Rossini and Boccherini, seemingly tirelessly, while the London Mozart Players tackled unfamiliar, tricky accompaniments, supporting their soloist both musically and emotionally through the experience. It was a real case of teamwork, with the cellist's personality and technique shining through.

05.04.18

When a member of the Primrose Quartet told me (in the departure lounge) that we would be using three different pianos for our recording of the Brahms Piano Quartets, my heart sank. We were facing the daunting prospect of recording two discs in the time normally allocated for one: the last thing I wanted was to spend valuable time performing an elaborate 'piano dance', shifting three grand pianos around each other on a small stage, not to mention balancing the sound afresh each day. But when pianist John Thwaites explained that all of these pianos had quite possibly been played by Brahms himself, in the very hall in Vienna where we would be recording, and that each had its own colours and characteristics, each suitable for a particular quartet, I soon overcame my misgivings and became excited to hear the results of this imaginative approach.

Day one, Quartet No 1, and we began with a gorgeous Blüthner, so softly coloured that any preconceptions of how one would normally balance a piano quartet flew swiftly out of the window. On day two this was replaced by a Streicher, the make of Brahms' own beloved piano, and which gave the Meridian engineer, Richard Hughes, slightly less of a headache. Finally, sounding far more similar to the pianos we hear today, was an Ehrbar, the manufacturer who built the stunning hall at the Prayner Konservatorium in which we were recording. John Thwaites was in his element, and it was fascinating for the rest of us to hear (and respond to) the effect of these different pianos upon the music. And, most importantly, we finished the recording on time!

15.03.18

Working with composers on session can engender a sense of trepidation. Will they want to take over proceedings? Will we get stuck in an interminable discussion on the minutiae of the score? Over the years I have shared the studio with Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, Michael Berkeley, Roxanna Panufnik and Cecilia McDowall, to name but a few, and I am pleased to say that they have been a delight to work with, achieving just the right balance of crucial artistic input and letting us 'get on with the job'.

This was no less the case with Andy Scott, whose works for saxophone and piano I recorded this month with Grammy Award-winner Tim McAllister and pianist Liz Ames. As with Alan Charlton (see January's post), Andy was part of the team: always on hand to answer queries from the musicians, or to point out any aspects of their interpretation that hadn't quite fulfilled his vision, yet relaxed enough to sit back and enjoy the emergence of a wonderful performance.

All of the compositions on the recording are firmly in the classical vein, yet coloured occasionally by elements of rock, jazz or Latin - influenced by Andy's own varied career as a saxophonist. Combine this with both mind-boggling virtuosity and soulful lyricism, and we have a truly wide-ranging account of what is possible from the modern-day saxophonist. I'd like to finish by mentioning the label releasing this recording, but as I write it is still up for grabs. Record company bosses, catch it before it's too late!

08.03.18

Today is International Women's Day, which leads me to muse on the role of women in music. As a female producer in a male-dominated industry, I am glad to say that I have rarely (to my knowledge) encountered sexism, one notable exception being a composer who, on discovering I was to produce his recording, uttered the memorable phrase, 'Oh. I was expecting a man', to which I wish I had retorted, 'Oh. I was expecting someone from the 21st century'.

Later this year I'll be recording with Tasmin Little a disc of works for violin and piano by women composers: Ethyl Smyth, the famous suffragette; Amy Beach, the acclaimed American pianist and composer whose performing career was curtailed, after her marriage, by cultural restrictions of the time; and Clara Schumann, one of the most influential pianists of the Romantic era. Married to Robert, who saw her as above all a wife and mother, Clara was also affected by attitudes of her era, saying of her compositions, 'naturally it remains woman's work, always lacking in strength and occasionally in ideas'.

This month, Chandos releases a recording which explores the music composed for 'Handel's last prima donna', Giulia Frasi, performed by soprano Ruby Hughes and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under Laurence Cummings. Frasi inspired not only Handel but many of his contemporaries to create roles for her; her 'sweet and clear voice' and 'smooth, chaste way of singing', engendering, as Ruby puts it, 'a depth of female characterisation which may well have subverted the norm at a time when women did not enjoy rights equal to those of men'.

During the recording sessions Ruby expressed surprise and pleasure that there were not one, but two women on the production team of three (Rosanna Fish was the assistant engineer). I'd like to think that people don't really care about my gender as long as I do the job properly, but it's still relatively unusual to see women in these roles. Over the years I have become more adept at making witty retorts to inappropriate comments, but, as the number of women entering the industry gradually increases, and as attitudes change, I hope that this skill will soon cease to be necessary.

06.01.18

A new year arrives and it's time to look ahead at the exciting projects in the diary. One thing that strikes me – and this is indicative of the way the recording industry is changing – is that more and more projects are initiated/funded by the artist, rather than being commissioned by record companies. This year almost a third of my recordings have been set in motion this way. Some artists already have labels lined up; others are hoping that the finished product will be sufficiently appealing or marketable to convince a record company to add it to their catalogue. It's a precarious path, with no guarantee that a recording will be snapped up, but when labels are tightening their belts and being ever more cautious about the marketing potential of new signings, few options remain.

One such artist-led project features the works of composer Alan Charlton. I should disclose at this point that Alan is a friend, but that doesn't make his music any less worthy of exploration. One of my earliest experiences of Alan's varied compositional style was on a choir tour to India in 2011 which coincided with that country's victory in the Cricket World Cup. Alan wrote a canon composed entirely of the names of Indian cricketers and it was an immediate hit, allowing kids of all ages to join with us in joyful song, simultaneously celebrating the achievements of their heroes.

That, of course, was a bit of fun, but Alan has composed a wide array of music in multiple genres, including the Suite for Cello and Guitar that we recorded last year, and 'The Cloud', a song cycle based on the poem by Shelley, to be recorded this Spring by soprano April Fredrick and pianist Will Vann. The latter is an astonishing piece of writing: composed within a new tonal framework devised by Alan, both piano writing and vocal line are imbued with a luminous quality which haunts the imagination long after hearing it. It is contemporary music with a quality and beauty unique to the composer: here's hoping that a record company snaps it up when the time comes.

29.11.17

One of the many things I love about my work is learning about the process behind-the-scenes to bring previously unheard music to the public ear. The last work ever composed by William Lloyd Webber was unearthed recently by his son, Julian, at the bottom of a drawer in the family home. He quickly passed it to violinist Tasmin Little, who was so entranced by this little gem that she adjusted the programming of her second ‘British Violin Sonatas’ disc for Chandos in order to include it.

That was a completely new discovery, but the efforts of the directors of Tempesta di Mare Baroque Orchestra in Philadelphia brought to light a collection of works that had once been known, but were later hidden from sight for decades and presumed lost.

Sara Levy (1762-1854) was a key figure in the Berlin music scene during the Prussian Enlightenment: a virtuosic performer, patron and collector of music, she was responsible for preserving hundreds of works, including a large number of compositions by members of the Bach family (Wilhelm Friedemann, eldest son of Johann Sebastian, was her teacher). After her death the majority of her collection was housed in the Sing-Akademie, but when this was plundered by the Red Army during World War II, it was considered lost for good. Discovered in Kiev and repatriated in 2001, the collection was a particularly rich trove of 18th and 19th century works, including two hundred Telemann cantatas and around 500 autograph manuscripts from the Bach family archive.

Of particular interest to Tempesta di Mare were dozens of pieces by the German Baroque composer Johann Gottlieb Janitsch, on whom they had already focused their attention as part of a recent concert series. Tempesta’s directors Gwyn Roberts and Richard Stone spent days at the Sing-Akademie, transcribing these works which had been feared lost for ever, and it is the fruits of those labours that can be heard on their latest recording for Chandos: Johann Gottlieb Janitsch: Rediscoveries from the Sara Levy Collection.

20.09.17

One wouldn’t normally compare Vivaldi’s Four Seasons with Harry Potter, but for me they share the curse of being so wildly popular that I was rather put off approaching them at all. Of course it’s impossible to avoid the Four Seasons, appearing as it does anywhere that ‘token’ classical music is required. But I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that, until two years ago, I could count on the fingers of one hand the number of times I had heard the work in its entirety.

Tasmin Little’s recording of the Vivaldi with the full string section of the BBC Symphony Orchestra was fresh, lively and vivid, the orchestra proving that large forces can still create all the required nuances. In the companion piece, ‘Four World Seasons’ by Roxanna Panufnik, each season is connected with a different country: Albanian Autumn; Tibetan Winter, etc. With no conductor (Tasmin directed from the violin), fiendish music and no previous knowledge of the score, the orchestra easily demonstrated why it is considered to be one of the best in the world.

With the Vivaldi score still in the cupboard, I was approached by Orchid Classics to record Max Richter’s ‘Four Seasons Recomposed’, written in 2012. Richter takes elements from the original Vivaldi and toys with them, looping fragments, changing rhythms or harmonies unexpectedly, even adding a certain ‘rock music’ feel to some passages, whilst always remaining completely recognisable as emanating from the original. Violinist Francisco Fullana and conductor Carlos Izcaray were perfectly matched, and the experience of recording the CBSO at Symphony Hall, Birmingham was something to be savoured.

10.07.17

It’s a natural part of the recording process to form a close professional relationship with the musicians one collaborates with. Working so closely together in such an intense environment, aiming towards the same goals, one can’t help but form a lasting bond. Indeed many producer/recording artist teams have endured for decades.

It’s not only people with whom we forge connections. It was twenty years ago that I first began recording at Potton Hall, a beautiful converted barn in the grounds of a rambling old manor house nestling in the Suffolk countryside. Retired Lotus-dealer and amateur organist Alan Foster had built the barn to house his collection of instruments: he loved to play his Compton theatre organ, complete with birdsong effects and flashing lights! It was sound engineer Trygg Tryggvason who saw the potential in the building and encouraged Alan to develop this warm, acoustically beneficial space into a recording venue.

Fast forward nearly two decades and Potton Hall is still a thriving concern, thanks in part to the vision of current owners John and Priscilla Westgarth. Under their watch, the estate has been updated and improved, with new facilities in both the recording studio and the house and grounds (spa facilities are free for anyone who records there). In re-launching the venue, they are now offering package deals to clients who don’t necessarily already have record deals in place, and I am delighted to announce that they have chosen me to provide these recording services for them.

06.04.17

With four recordings in three countries and two continents, March was not going to be relaxing! The projects weren’t just geographically diverse: with repertoire spanning two-and-a-half centuries and ensembles encompassing two choirs, two chamber orchestras, a piano, an organ and two baroque quartets, I certainly couldn’t complain about lack of variety!

First on the list was a recording of Mozart’s Piano Concertos, with Jean-Efflam Bavouzet and the Manchester Camerata, conducted with inimitable style by Gábor Takács-Nagy. I’m not sure I’ve heard a conductor use so many visual analogies to inspire his players (‘play as though you are champagne fizzing from the bottle’), but it was clear that he sparked their imagination and the result was a performance of stylish refinement and joy.

Next was a trip to Philadelphia, working with the baroque ensemble Tempesta di Mare on a recording of works by German baroque composer Johann Gottlieb Janitsch, the story of which I shall tell in another post. I have collaborated with this ensemble so many times now that it feels like visiting old friends.

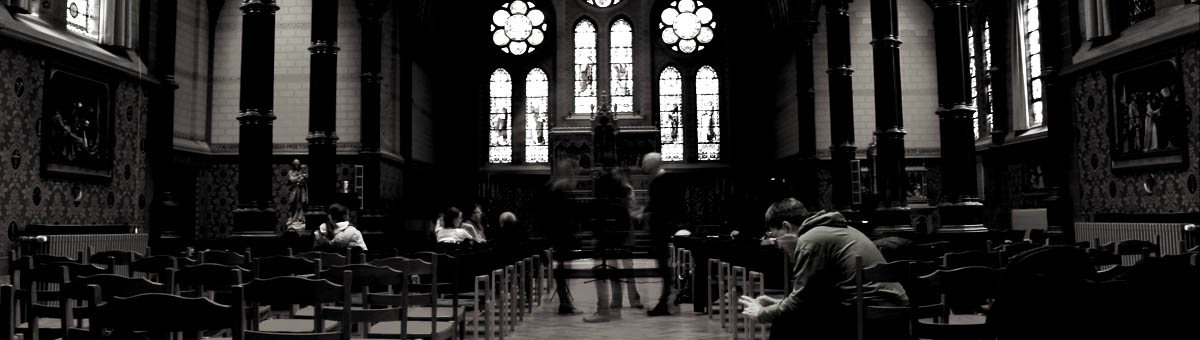

For a recording of contemporary Belgian choral works with the Brussels Chamber Choir, Helen Cassano, their conductor, had managed to find the most glorious recording venue, in the form of a chapel hidden away inside a school in the Flemish countryside. Gorgeously ornate, and with a stunning acoustic, it was apparently only used these days for the funerals of nuns! Fortunately, all the nuns remained alive in the week leading up to the recording, and so we were able to record without interruption.

The greatest pleasure for me during that weekend was to record two works by my friend Alan Charlton, whose music deserves far wider recognition. I hope that our recording for Etcetera will go some way to remedy this.

The final recording of the month was of Christmas music, which of course one always has to record at some unseasonable time of year. The chapel choir of Bedford School is directed by Jeremy Rouse, who was organ scholar at Girton College, Cambridge during my time as a choral scholar there. It was great fun to give the boys their first experience of recording. I think they had started the week congratulating themselves on being allowed off lessons, thinking that recording would be a ‘bit of a doss’. That illusion didn’t last for long, oh no!

28.02.17

Having travelled extensively in the earlier part of the year, I was pleased that my next recording was just an hour’s drive away – at Potton Hall, a glorious converted barn in the heart of the Suffolk countryside. Michael Collins and Michael McHale were tackling the Reger Clarinet Sonatas; a challenge both musical and technical that they pulled off with consummate ease.

I was able to catch up with editing various projects, including the sixth instalment of Haydn’s Piano Sonatas on Chandos, impeccably performed by Jean-Efflam Bavouzet. Over the past few years we have been recording the complete sonatas of both Haydn and Beethoven concurrently, but now that the latter series has come to an end, we are able to give our full attention to Haydn. The sessions are always very intense, but we also have a great deal of fun together. For this recording, Yamaha had shipped over two pianos for Jean-Efflam to choose between. Still full of beans at the end of the sessions, and with both pianos still in place, he suggested that we line them up side by side and attempt to play a Haydn movement with the right hand on the right piano, and the left hand on the left one. Except that this meant that the right hand was playing the left hand’s music, and vice versa. Sound confusing? It was! As if it wasn’t stressful enough sight-reading Haydn with my brain left-right reversed in front of a renowned concert pianist, I was then encouraged to play Bach’s C minor Prelude from memory whilst lying flat on my back with my hands crossed behind my head… well, no one can say I don’t relish a challenge!

02.02.17

The year began with a flurry of activity (not to mention snow), as I flew to New York to record piano concertos by German composer Ferdinand Ries at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson. Piers Lane had performed the 8th concerto at Carnegie Hall with Bard’s newly-formed training orchestra, ‘The Orchestra Now’, and saw the opportunity to give the orchestra vital recording experience, whilst adding to Hyperion’s ‘Romantic Piano Concerto’ series. The conductor was Leon Botstein, eminent musicologist and President of Bard College, who likened recording to going to the dentist. I don’t think it was anything personal…

Only a few days to recover from jet lag, then off to Dublin to meet Bill Whelan, the composer of Riverdance, and Sir James Galway. We were recording the fruits of their first collaboration: Linen and Lace, for the RTÉ lyric fm label. The flute concerto (here performed by the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra under David Brophy), is inspired by the birthplaces of soloist (Belfast) and composer (Limerick). The towns are renowned for their linen and lace respectively, and this work interweaves several aspects of their musical traditions.